![Downfall_l]() DIRECTOR: Oliver Hirschbiegel

DIRECTOR: Oliver Hirschbiegel

CAST:

Bruno Ganz, Alexandra Maria Lara, Corinna Harfouch, Juliane Köhler, Ulrich Matthes, Thomas Kretschmann, Christian Berkel, Matthias Habich, Heino Ferch, Michael Mendl, André Hennicke, Ulrich Noethen, Doneven Gunia, Thomas Thieme

REVIEW:

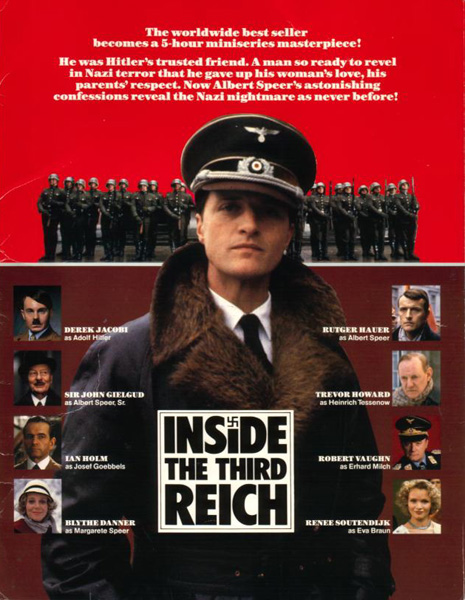

The third major film depiction of the last days of Adolf Hitler (following 1973’s Hitler: The Last Ten Days, starring Alec Guinness, and 1981’s The Bunker, starring Anthony Hopkins) but the first internationally-released German production to feature Hitler as a main character, Downfall is director Oliver Hirschbiegel and screenwriter Bernd Eichinger’s frank confrontation of a man and legacy that has stigmatized and haunted Germany for sixty years. Based on German historian Joachim Fest’s book “Inside Hitler’s Bunker” and Hitler’s secretary Traudl Junge’s own memoirs “Until the Final Hour”, Downfall validates the notion that perhaps, despite their reluctance, it was up to the Germans to make the first truly convincing Hitler film. The results speak for themselves: Downfall is a well-crafted, morbidly engrossing, and occasionally wrenching war drama bolstered by an extraordinary lead performance by Bruno Ganz.

Downfall is bookended with brief snippets of interviews with Traudl Junge conducted shortly before her death in 2002, and the film uses Traudl as our entry point, starting with a prologue in November 1942 as the young secretary (Alexandra Maria Lara) is appointed to the Führer’s headquarters. We next skip to April 1945, with Traudl and the rest of the entourage (an assortment of secretaries, cooks, aids, and top Generals) holed up with Hitler (Bruno Ganz) in his bunker beneath the Reich Chancellery in Berlin, which is now almost surrounded by the Russians, who are overrunning the city’s outskirts and pounding the rest into rubble. Many of the Führer’s underlings, including Heinrich Himmler (Ulrich Noethen) and Eva Braun’s brother-in-law Hermann Fegelein (Thomas Kretschmann) urge him to flee, but Hitler is determined to stay in the besieged capital, still holding out hope for a last minute turn in the tide, and if that fails, resolving to kill himself in the bunker. Many of his subordinates have already fled, and those who remain, including Traudl, are anxious to get out before it’s too late, but a small circle of diehard loyalists join Hitler in the bunker, including Eva Braun (Juliane Köhler), the Führer’s vacuous mistress, and the Goebbels family, led by Nazi Propaganda Minister Josef Goebbels (Ulrich Matthes) and his wife Magda (Corinna Harfouch), both of whom are willing to sacrifice not only themselves, but their own six children. Surrounded by this shrinking inner circle, Hitler becomes more and more disconnected from reality, moving armies around that exist only on his maps, refusing to evacuate the civilian population, and throwing frenzied rages when nonexistent forces do not come to the rescue. Outside, last-ditch fighting pits old men and schoolboys against Russian tanks, including Hitler Youth Peter Kranz (Donevan Gunia). SS physician Ernst-Günther Schenck (Christian Berkel) resolves to stay in Berlin to do what he can to care for the wounded and civilians. General Helmuth Weidling (Michael Mendl) is given the hopeless duty of defending Berlin, much to his chagrin. The hard-nosed SS General Wilhelm Mohnke (André Hennicke) is personally willing to fight to the last bullet but disapproves of schoolboys being sent into combat. But the lion’s share of the movie takes place inside the labrynthine corridors and dimly-lit rooms of the claustrophobic, suffocating bunker, as the atmosphere grows increasingly unrealistic and unhinged, until time finally runs out and the Third Reich dies in an orgy of suicide, murder, and devastation.

Downfall was accompanied by significant controversy, much but not all of it taking place in Germany, about whether its portrayal of Hitler was “too sympathetic”. Hirshbiegel and Eichinger have striven for rigorous historical accuracy and a frank, docudrama-style depiction of events without melodramatic exaggerations or over-the-top histrionics. Even the most disturbing characters–Hitler and Magda Goebbels–are not depicted with horns and forked tails or breathing fire. Hitler’s famous (and sometimes exaggerated) rages are few and far between, and even then, Bruno Ganz does not go the cartoonish lunatic approach of many Hitler performers. But an accusation that the movie portrays Hitler sympathetically seems to me that it must come from one who has not watched it. Ganz’s Hitler shares a liplock with Eva Braun, once comes to the verge of tears, is a considerate boss to his secretaries, and from beginning to end, he is kind to Traudl Junge, but the overall depiction is not a flattering one. Moments of kindness aside, Hitler is shown throughout to be a cold-hearted, hateful, unstable, and self-absorbed figure veering between wallowing in self-pity and flaring up into bursts of rage. He seems to grow more delusional and paranoid by the day, grasping desperately at straws and seeing traitors everywhere, lashing out irrationally and tossing his own brother-in-law Fegelein to the firing squad on “evidence” that is flimsy at best. When told that young German soldiers are dying in the thousands for a lost cause, he shrugs and says with searing callousness that that’s what young men are for. To him, the German people are no longer fit to live because they have proven themselves weak, and “I will not shed one tear for them”. If he is capable of shedding tears at all, it is apparently only for himself.

![downfall2]() Alone among the many, many actors who have played Hitler over the decades, acclaimed Swiss actor Bruno Ganz achieves the herculean task of allowing us to forget for over two hours that we are watching an actor playing a role. This is every bit as impressive, if not more so, an example of an actor embodying a historical figure as George C. Scott in Patton or Daniel Day-Lewis in Lincoln (both of which received an Oscar while Ganz was not even nominated), in an even more difficult and controversial role. Part of it is that Downfall is German-language; no matter how tremendous the performance of, say, Anthony Hopkins might be, Hitler with Hopkins’ voice just doesn’t quite compute, any more than an actor playing FDR would be completely convincing speaking German. Ganz has the voice, body language, and mannerisms down almost perfectly, and while not a dead-ringer, the makeup job is more than adequate, but those are all scratching the surface. The real triumph of Ganz that he plays Hitler not as an over-the-top caricature, but as a three-dimensional, albeit loathsome, individual. Ganz manages the mighty feat of occasionally bringing us to the brink of feeling a scrap of pity for the physically and spiritually broken dictator, then in the next moment tossing out a comment of chillingly casual heartlessness and making us feel disturbed about how close we came. His colossal rages are few and far between, interspersed by lethargic lounging around and rambling about everything from the best ways to commit suicide (he and Eva argue over cyanide versus a gun) to the senselessness of compassion, to poring over his unfulfilled architectural designs for a remodeled, grandiose Berlin, but when they do come, they are wild and frothy, spewing spittle, thumping tables, railing about treachery and weakness from all around him. Ganz’s performance is a powerhouse tour de force with a chilling sense of authenticity, and easily the most convincing Adolf Hitler ever played by an actor.

Alone among the many, many actors who have played Hitler over the decades, acclaimed Swiss actor Bruno Ganz achieves the herculean task of allowing us to forget for over two hours that we are watching an actor playing a role. This is every bit as impressive, if not more so, an example of an actor embodying a historical figure as George C. Scott in Patton or Daniel Day-Lewis in Lincoln (both of which received an Oscar while Ganz was not even nominated), in an even more difficult and controversial role. Part of it is that Downfall is German-language; no matter how tremendous the performance of, say, Anthony Hopkins might be, Hitler with Hopkins’ voice just doesn’t quite compute, any more than an actor playing FDR would be completely convincing speaking German. Ganz has the voice, body language, and mannerisms down almost perfectly, and while not a dead-ringer, the makeup job is more than adequate, but those are all scratching the surface. The real triumph of Ganz that he plays Hitler not as an over-the-top caricature, but as a three-dimensional, albeit loathsome, individual. Ganz manages the mighty feat of occasionally bringing us to the brink of feeling a scrap of pity for the physically and spiritually broken dictator, then in the next moment tossing out a comment of chillingly casual heartlessness and making us feel disturbed about how close we came. His colossal rages are few and far between, interspersed by lethargic lounging around and rambling about everything from the best ways to commit suicide (he and Eva argue over cyanide versus a gun) to the senselessness of compassion, to poring over his unfulfilled architectural designs for a remodeled, grandiose Berlin, but when they do come, they are wild and frothy, spewing spittle, thumping tables, railing about treachery and weakness from all around him. Ganz’s performance is a powerhouse tour de force with a chilling sense of authenticity, and easily the most convincing Adolf Hitler ever played by an actor.

![downfall3]() Alexandra Maria Lara adds a needed dash of comparative normalcy and humanity as the impressionable Traudl Junge, who wants to believe in the Führer but witnesses the events around her with mounting horror. “It’s all so unreal,” she despairs at one point, “like a dream where you can’t ever wake up”. The audience will inevitably gravitate toward her as one of the only remotely sympathetic characters, making her an effective entry point into the bunker. Ulrich Matthes plays Josef Goebbels as an icy fanatic, but he’s surpassed by the chilly Corinna Harfouch as his wife Magda, an ice queen with a will of steel so unshakably devoted to Hitler that to her warped mindset, killing her children with her own hands is kinder than leaving them to grow up in a world without Nazism, which she likens to a world without sunshine. Juliane Köhler plays Eva Braun as a vacuous party girl, laughing and dancing as though nothing is happening, but we suspect that this is her way of blocking out the grim reality. Her adored Adolf’s insanity and venom should be obvious to anyone, let alone his longtime mistress, but Eva either cannot see it or–perhaps more accurately–simply refuses to. Heinrich Himmler drops by early on, played by Ulrich Noethen as a deluded self-important twit clueless enough to wonder whether he should give General Eisenhower the Nazi salute or shake his hand. Heino Ferch is the dapper, inscrutable architect Albert Speer, who urges Hitler not to go through with his plans for total destruction but remains an enigmatic figure. He’s obviously the most level-headed, composed, and realistic of the high-ranking Nazis, but he never wears his feelings on his sleeve, and we’re never entirely sure what’s going on inside his head. The only member of the inner circle whose portrayal is a little disappointing is Martin Bormann, played by the buffoonish-looking Thomas Thieme, who despite generally being regarded as one of the most influential members of Hitler’s court, has so little screentime and dialogue that he seems to barely be in the movie.

Alexandra Maria Lara adds a needed dash of comparative normalcy and humanity as the impressionable Traudl Junge, who wants to believe in the Führer but witnesses the events around her with mounting horror. “It’s all so unreal,” she despairs at one point, “like a dream where you can’t ever wake up”. The audience will inevitably gravitate toward her as one of the only remotely sympathetic characters, making her an effective entry point into the bunker. Ulrich Matthes plays Josef Goebbels as an icy fanatic, but he’s surpassed by the chilly Corinna Harfouch as his wife Magda, an ice queen with a will of steel so unshakably devoted to Hitler that to her warped mindset, killing her children with her own hands is kinder than leaving them to grow up in a world without Nazism, which she likens to a world without sunshine. Juliane Köhler plays Eva Braun as a vacuous party girl, laughing and dancing as though nothing is happening, but we suspect that this is her way of blocking out the grim reality. Her adored Adolf’s insanity and venom should be obvious to anyone, let alone his longtime mistress, but Eva either cannot see it or–perhaps more accurately–simply refuses to. Heinrich Himmler drops by early on, played by Ulrich Noethen as a deluded self-important twit clueless enough to wonder whether he should give General Eisenhower the Nazi salute or shake his hand. Heino Ferch is the dapper, inscrutable architect Albert Speer, who urges Hitler not to go through with his plans for total destruction but remains an enigmatic figure. He’s obviously the most level-headed, composed, and realistic of the high-ranking Nazis, but he never wears his feelings on his sleeve, and we’re never entirely sure what’s going on inside his head. The only member of the inner circle whose portrayal is a little disappointing is Martin Bormann, played by the buffoonish-looking Thomas Thieme, who despite generally being regarded as one of the most influential members of Hitler’s court, has so little screentime and dialogue that he seems to barely be in the movie.

The most disturbing scene Downfall has to offer does not even involve Hitler. It is Magda Goebbels committing the most unthinkable act possible for a mother: the murder of her own six children. The scene is eerily non-violent; having already given them a sleeping pill, she methodically goes from one to the next cracking cyanide capsules inside their mouths. It’s a truly disturbing scene, one which many viewers will find difficult to watch despite its low-key, matter-of-fact bloodlessness. A fraction of a second in which Magda’s face of stone threatens to crack makes her more human but not more sympathetic, instead a sad, sick, horrifically deluded woman. While no other scene matches the horror of this one, there are various other moments of graphic violence that recall those in the likes of Saving Private Ryan: various characters shooting themselves in the head, wounded soldiers getting limbs sawed off, blood soaking walls and floors. By the end, the bunker has become a tomb. Along with such films as The Pianist, Downfall, ironically filming in Russia with St. Petersburg standing in for 1945 Berlin, convincingly recreates a city devastated by war. Possibly to avoid offending their Russian hosts, the filmmakers gloss over the widespread rapes committed against German civilians by Russian soldiers, and the epilogue is perhaps implausibly idealized, but by then it comes as a welcome slight ray of sunshine after the two hours of madness, brutality, and destruction.

While Downfall is a must-see for many WWII buffs, its mainstream appeal is dubious–a group of detestable characters hole up in a bunker and eventually kill themselves–and the film is as far from “uplifting” or “feel good” as anything to be found. But to those with an interest in the subject matter, it is one of the most finely-crafted WWII dramas ever made, by far the best onscreen depiction of the last days of Adolf Hitler, and a forceful, searing experience that can leave one thinking about its subject matter long after the credits roll.

* * *1/2

For the most part, Dustin Hoffman, who tends to be at least a little theatrical at the best of times, is solid, although there are moments when his histrionics get a little excessive. We sympathize with Babe, which is important. Roy Scheider is solid as his enigmatic brother, as are Marthe Keller and William Devane, who keep us uncertain about their ambiguous characters. The late Richard Bright, a familiar henchman type (he was the Corleone hitman Al Neri in all three installments of The Godfather) and Marc Lawrence are Szell’s cronies. Fritz Weaver has essentially a cameo as Babe’s brilliant professor Biesenthal. Best, unsurprisingly, is Sir Laurence Olivier, who brings a smooth, cultivated viciousness to his sinister role, using a calm, cold demeanor and eyes that never seem to smile even when his mouth does, to make Szell a thoroughly menacing villain (Olivier was nominated for an Academy Award). The infamous scene in which he casually uses dentist’s tools as torture devices to extract information from a helplessly squirming Babe is the stuff of cinematic legend, and thirty years later, while not particularly graphic, it remains uncomfortable to watch. This features Marathon Man at its strongest.

For the most part, Dustin Hoffman, who tends to be at least a little theatrical at the best of times, is solid, although there are moments when his histrionics get a little excessive. We sympathize with Babe, which is important. Roy Scheider is solid as his enigmatic brother, as are Marthe Keller and William Devane, who keep us uncertain about their ambiguous characters. The late Richard Bright, a familiar henchman type (he was the Corleone hitman Al Neri in all three installments of The Godfather) and Marc Lawrence are Szell’s cronies. Fritz Weaver has essentially a cameo as Babe’s brilliant professor Biesenthal. Best, unsurprisingly, is Sir Laurence Olivier, who brings a smooth, cultivated viciousness to his sinister role, using a calm, cold demeanor and eyes that never seem to smile even when his mouth does, to make Szell a thoroughly menacing villain (Olivier was nominated for an Academy Award). The infamous scene in which he casually uses dentist’s tools as torture devices to extract information from a helplessly squirming Babe is the stuff of cinematic legend, and thirty years later, while not particularly graphic, it remains uncomfortable to watch. This features Marathon Man at its strongest.